|

Richard Birdsall Rogers

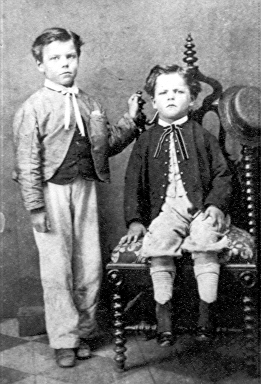

Richard Birdsall Rogers was born in Ashburnham, Peterborough, Ontario on January 16, 1857, son of Robert David Rogers and Elizabeth Birdsall Rogers, daughter of Richard Birdsall, P.L.S. He was born into a family of 9 children. The Rogers' siblings were: Eliza Maria (b. 1841), James Zacheus (b. 1842), Sophia Louisa (b. 1844), Maria McGregor (b. 1845), Amelia Mary (b. 1848), George Charles (b. 1854), Richard Birdsall (b. 1857), Edwin Robert (b. 1859) and Alfred Burnham (b.1864). Amongst Rogers' ancestors

on both sides of the family were members who were known for

their heroic efforts in times of war, founding settlements,

and entrepreneurial activities. |

||||||||||||

|

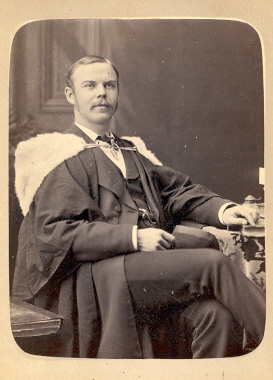

Rogers was educated at the Union School in Peterborough and later attended Trinity College School, Port Hope (early 1870's). At the age of 17 Rogers left his family home for Montréal, Québec to study at McGill College. Rogers boarded at several different homes during his studies and he mentioned his hosts frequently on Montréal outings and friendly calls. He chronicled this time in great detail in diaries and letters and described dividing his time between study, socializing and sports. He continued to play sports even on his visits home and often went to Port Perry and nearby locations for matches. In his early diaries he copiously recorded how long he spent with his studies each night and the time he went to bed. In his 1874 Diary, Rogers made a list of 12 Resolutions which he considered would improve his character. He later added to these original resolutions in his 1876 Diary with two inserts entitled "Daily Routine" and "After Convocation" (1878). On visits home he frequently called on several families in the community and one family, the Henry Calcutts, received much of his attention during socializing. The Calcutts were a prominent family known for their Calcutt Brewery (now the site of Lion's Pool) and their children, primarily Addy and later Mina, became good friends of Rogers'. During these earlier years most of the visits with the Calcutts included much time spent with Addy Calcutt (older sister of his future wife). In those early years Mina was scarcely mentioned in his writings as she was younger in age than both Rogers and Addy. Addy soon left for school however, and the friendship, though close, did not grow into love. |

||||||||||||

|

His growing acquaintance with the Calcutts did bring about love with the younger Calcutt daughter Mina, also of Ashburnham. Story has it that Rogers sold his sports trophies to buy the engagement ring for Mina. They finally married on February 24th, 1881 shortly after Richard's 24th birthday. Richard and Mina's children were: George Charles (b. 1883, d. in infancy), Harry George (b. 1884), George Norman (b. 1886), Edna Isabella (b. 1888), Lillian Kate (b. 1890), Leah Muriel (b. 1892) and Heber Symonds (b. 1895) and there is mention of another child having died in infancy early in their family life.

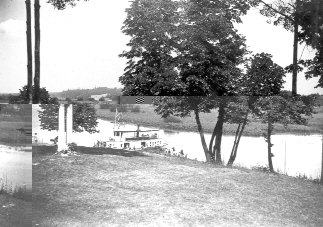

In 1884 he was appointed Superintending Engineer of the Trent Canal, a position which he held until his retirement in 1906. While serving as Superintendent of the Trent Canal, Rogers suggested the use of hydraulic lift locks to the Minister of Railways and Canals, Hon. John Haggart. The Department became interested in the new hydraulic system of locks and commissioned Rogers to travel to Europe to study existing locks there. He left for Europe in February of 1896, planning to visit sites in France, Belgium and England. His tour consisted primarily of the lock at La Fontinette in Southern France, the lock at the La Louvinière, in Belgium, and the lock at [Norwich], England with a few stops at smaller sites as mentioned in his 1896 Diary. Rogers obtained several letters of introduction to meet the Engineers in charge of the works in Europe. Although some of the engineers were too busy to see him, he did speak to others and tried his best to visit the sites and look over their plans. Some of the engineers allowed him access to much of the necessary information and Rogers, armed with this new-found knowledge, returned to Canada. Once home, he was able to convince the Department of Railways and Canals to allow him to proceed with the plans for construction. Rogers laid out the general plans and from there his staff, mainly Walter J. Francis, his Chief Draughtsman and Thomas A.S. Hay, completed the superstructure and substructure plans under Rogers who Superintended the project.

During the construction of the Hydraulic Lift Lock, Rogers worked within a complex matrix of bureaucratic structures. He wrote reports and attended endless meetings to get permissions. Once the project was approved he found himself constantly summoned to Ottawa and Montreal to meet with authorities who demanded updates on the project. At the beginning of the work, Rogers found that he had some important and valuable supporters in the government specifically in Mr. Collingwood Schreiber, Chief Engineer of the Department of Railways and Canals, who corresponded with him on all matters relating to hiring of personnel and labourers, and on technical specifications. Mr. Schreiber was also the contact person in Ottawa for Rogers' reports. He advised Rogers on many matters and was consulted in the many changes that were ordered by the government. Rogers also had to contend with the many people who had input into the construction of this important and costly work. During this period in his life, Rogers related how occupied he was travelling back and forth between the numerous constructions sites, while simultaneously driving between Peterborough, Ottawa and Montreal, to name just a few places, to get decisions approved, to explain his methods of construction and just to reassure the authorities that the project was indeed progressing at a satisfactory pace.

One of two main contractors on the Works was Corry and Laverdure. The company excavated the site and built the concrete towers and lock.The other contractor was Dominion Bridge of Montreal which was hired to do the metal work including the rams, presses and large caissons of the lock. During the construction of the locks it is no wonder that Rogers

made little or no references to family and friends in his personal

papers or journals. He poured, instead, over details of the investigations

and inspections of the sites which slowly took over his life.

The Peterborough Hydraulic Lift Lock officially opened in 1904 to great ceremony and fanfare with the Minister of Railways and Canals Hon. Henry Emmerson presiding and with the Postmaster General William Mulock in attendance. The Kirkfield Lock opened in 1906. Shortly thereafter, the bright light of Richard Birdsall Rogers started to dim. A disagreement over budgets with Corry and Laverdure ensued after they started to work on the Hydraulic Lift Lock. After that, Rogers continued to deal with claims from Corry and Laverdure relating to the many changes that the works required. Many of the claims concerned the "dry pour" method of concrete mixing that Rogers planned for the Works. The method which was innovative at the time, was also costly and required a great deal more time to complete than other methods of the day. The fact that the team was also pioneering the system, and that they had little or no experience with dry-pour, also caused the contractors and engineers to experiment much of the time and this in turn gave rise to the many claims about what was defined as extra work and what constituted part of original contracts. The contractors contended that they should be paid extra for all the additional work and Rogers insisted that all the necessary work was included in the contract already and he refused to pay them any more money. At the height of the disputes, the government assigned a Commissioner to investigate the claims. Mr. Henry Holgate was assigned the job of inspecting the Works in 1906. Prior to the Holgate Report the popular opinion of the Works seemed very different from that after the Report was released. Because of this much publicized report, as well as changes in government, Rogers saw himself less and less in the favour of the government. Unfortunately, the government decided to support the contractors and awarded their claims. Rogers soon found himself blamed for going over-budget on the project. It was thought at the time that the scandal involved not only budget costs between Rogers and the contractors, but also other political issues. Rogers was originally appointed Superintending Engineer by the conservative government of Sir John A. Macdonald and there is little doubt that his position as a public servant involved in public works became compromised even as early as governments changed. The Holgate Report charged that Rogers made erroneous technical decisions and mistakes in budgeting his work. In response to the investigators, Rogers insisted that his work had been performed appropriately. It was to no avail, despite his repeated requests for another investigation. The media of the day used this situation to great advantage and soon a great man was disgraced. After the release of this Report, the Minister of Railways and Canals asked for Rogers' resignation in a letter dated February 14, 1906. Rogers tendered his letter of resignation in a handwritten note on February 19th. Walter J. Francis replaced Rogers as Superintending Engineer. Francis later resigned himself to move to British Columbia. Years later, in conjuction with changes that occurred in government, Rogers managed to ignite new interest in his situation and finally was given an opportunity to be heard. After promising to foot the bills for a new investigation, the new minister, Hon. Frank Cochrane, appointed another commissioner, Mr. Charles H. Keefer, M.A.S.C.E., who was also the President of the Canadian Society of Civil Engineers. Mr. Keefer was commissioned to investigate both the Holgate Report and Rogers' side of the story. Keefer reviewed all the allegations in the construction of the Hydraulic Lift Locks at Peterborough and Kirkfield and his investigation, when it was concluded, completely vindicated Richard Birdsall Rogers as Chief Engineer. Furthermore, Mr. Keefer's Report found that Holgate's investigation and report had been conducted and heavily influenced by political preferences instead of basic engineering practices. The Report was released in 1914 to Rogers’ great relief and letters of congratulations soon started pouring in from all his friends in the community. Ironically, the government took Rogers at his word and insisted that he pay the bill for the investigation. Correspondence is found in our collection in which Rogers protested having to pay Mr. Keefer’s bills in light of the findings in his favour. Political pressure soon overwhelmed Rogers and despite his own money worries at the time and all his protestations to avoid the payment, on April 3, 1915, Rogers gave in. He sent the cheque for $1150.00 and paid the bill for his vindication. Undoubtedly, these repeated attempts at defending himself took their toll on Rogers' health and ego but he did enjoy vindication during his lifetime, however late and long in coming that it was.

After his retirement from government service, Rogers was associated with Smith, Kerry and Chase and was involved with the firm's projects on the Trent River. At the time, he was in charge of the Campbellford plant of the Northumberland Pulp and Paper Company. He purchased the Campbellford Mill with some friends and attained a controlling interest of the company. The products the Mill supplied were strawboard, mill board and house sheeting. A news clipping also mentioned that located on the property of the Mill was "one of the greatest water powers in Ontario" which was not fully developed at the time Rogers acquired it. Rogers then decided to move to Campbellford in 1906 to manage the company. Shortly after, on the 21st of February that year Mr.William Dennon accepted to form a partnership with Rogers and the firm of Dennon and Rogers completed several contracts along the Canal. The partnership lasted only 10 years and was dissolved in 1916. During the First World War, Rogers not only had two sons fighting for their country but he himself chaired a recruiting committee of 5 citizens to do his part for the war effort. He sent letters to the editor of the local paper to try and help the cause. He stayed in Peterborough until 1916 and then retired. He moved to Beechwood Farm in the Township of Douro, which is now site of the Peterborough Golf Club. During his later years, Rogers kept active in social and community affairs and continued to be active until his death on Oct. 2nd, 1927 . His wife, Mina died a few months earlier in May after battling a long illness. During his life, Rogers belonged to the Engineering Institute of Canada and to the Institute of Civil Engineers of London. He is buried in Little Lake Cemetery with his headstone facing Peterborough Hydraulic Lift Lock.

|

||||||||||||

Information Sources and Bibliography

Cole, Jean Murray, ed.The Peterborough Hydraulic Lift Lock. Peterborough: Friends of the Trent-Severn Waterway, 1987.

Jones, Elwood and Bruce Dyer. Peterborough: The Electric City: An Illustrated History. Burlington: Windsor Publications, 1987.

Kidd, Martha Ann. Historical Sketches of Peterborough. Peterborough: Broadview Press, 1988.

The Unsung Genius Who Built the Lift Locks by Alicia Perry (Peterborough Historical Society, March 15, 1977 & The Peterborough Common Press, Tuesday March 22, 1977)

Extract from: Annual Report of the Association of Ontario of Land Surveyors, by Mr. Willis Chipman. Held in Toronto Feb. 21st & 22nd, 1928.

Perry, Alicia. The Lift Lock Story. An Occasional Paper. Peterborough: Peterborough Historical Society, 1980.

Rogers Family Memoirs, Compiled [1875] by R.Z. Rogers and reprinted 1895

Rogers, Richard Birdsall. Papers, Correspondence, Diaries 1884-1915 and other materials found at Trent University Archives in the Geale-Rogers Collection (82-022)

Pamphlet : Rogers Building 1856. [Peterborough]: Quaker Oats Company, 1988.

Wells, Kenneth McNeill. Cruising the Trent-Severn Waterway. Toronto: Kingswood House, 1959.