The Trent Valley Canal Project:

Promises of Prosperity

The waterways which laced the old Newcastle District were a critical and effective means of moving around the Kawarthas for Aboriginal inhabitants. They were also necessary for getting new European immigrants to the back townships around Peterborough but presented many challenges to the transporting of people, personal effects, furniture, livestock, agricultural tools and food as the rivers were filled with shoals, narrows, and precipitous drops. The name of the Otonabee river, which flows down from Lakefield through the city of Peterborough to Rice Lake, is an anglicised version of the aboriginal name meaning "swiftly moving and dangerous water." The section between Lakefield and Peterborough was called "The Nine-Mile Rapids" for good reason. Travel by the inexperienced and the ill-prepared was fraught with danger. It necessitated many overland portages and many overnight stays in less than comfortable conditions. Travelling in winter by sleigh over bush roads and across frozen lakes was only somewhat better and was not an option in the earliest days of European settlement. Frances Stewart remarked on her proposed trip with her family up to Douro Township in Upper Canada in November, 1822:

|

Our house is not ready yet, so we must live in a shanty or hut or for some days till it is ready; what causes so much hurry, is the danger of ice forming on a lake we must cross; this Rice Lake is scarcely ever open after the 20th of this month, it is at this moment freezing, so that we are afraid it will not be fit to boat across on saturday – in which case we must remain here till it is hard enough for sleighing... |

In fact it was the next spring that the Stewarts finally made it to their new log cabin. British immigrants continued to straggle in during the early 1800s. And it has been noted that the immigrants were drawn to the backwoods as much by the promise of the waterways as by the free land since, "A water system meant not only mill sites and possible water rights but also a convenient means of transportation and the inexpensive movement of valued commodities like lumber.(1) The influx of Irish immigrants to the Peterborough area and the surrounding townships of Ops, Emily and Cavan in 1825 put new pressures on the roads and waterways. Bush roads were rudimentary and for weeks at a time in the spring season, they were impassable. With the ice going out of lakes and sleighing season over, moving around newly settled areas was difficult. Now too, as well as providing access for new settlers, there was a perceived need which increased year by year to provide for the transport of lumber and other goods out of the back townships to urban markets in Canada and the United States. Burgeoning towns and a pioneering entrepreneurial spirit drove the political pressure for improved communications systems throughout the nineteenth century. The Age of the Canal was first. The 1830s and 40s saw many canal projects begun, some completed, and some abandoned as the Age of the Railway took over in mid-century, until it too gave way, this time to the automobile. Notwithstanding the impact of railways, canals and waterway transportation were seen by many proponents as the most efficient route to external markets and, thus, prosperity for the hinterland. Though enthusiasm for canals waxed and waned with successive governments, the importance of canals continued to be discussed until well into the twentieth century.

|

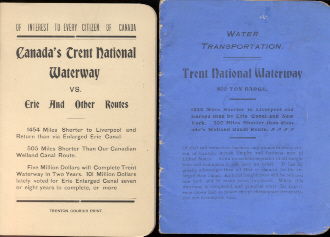

Pamphlets from Lectures

|

|

|

Canal Works Frankford, Ontario 3

|

In addition to transporting settlers and goods in, and lumber and agricultural produce out, waterways were seen as intrinsic features of recreation very early on. After the collapse of the lumber market in 1873, leisure activities and tourism became even more important. Several canoe building companies were located in Peterborough. Steamship companies such as Mossam Boyd’s Trent Valley Navigation Company, P.P. Young’s Stoney Lake Navigation Company, and Henry Calcutt’s Peterborough Steamboat Navigation Company toured the lakes and took people on picnics, to regattas, out in the country for hunting and fishing, for day excursions, and they provided local transportation for people and freight. The steamboat owners also built lodges and resorts in the Kawarthas. There were strong interconnections between roads, steamboats and railways and an integrated transportation system developed through the 1880s and 1890s though hampered, as some argued, by the inability to navigate all the way through the Trent-Otonabee-Severn waterway system.

The first lock to be built in the Kawartha area was at Bobcaygeon. Work on this was completed in 1833 but it took the rest of the century, and then some, to complete a navigable inland water route which linked Lake Ontario and Lake Huron. From the 1820s through the 1830s, men like John Beverley Robinson and John Strachan were convinced of the limitless possibilities of water transportation with the "spirit of improvement" impelled by envy of the big canals in the United States fuelling the canal-building era.(2) But there were periods of resistance from both Liberal and Conservative governments and from both federal and provincial legislatures with the most sustained interest arising from local proponents. It took nearly 90 years to complete the ditching and locking of the Trent-Severn system. Locks were begun at Young’s Point in 1869. By 1887, there were locks at Burleigh Falls, Lovesick Rapids, Buckhorn and Fenelon Falls (3) but the greatest challenge lay ahead: the Nine-Mile Rapids south of Lakefield and the huge drop at the city of Peterborough. One of the labourers who worked on the dredging of the canal reported that a log boom started in Lakefield would reach Peterborough in one hour.(4) A major incentive to the project came in 1891 when the United States government passed rigid protectionist legislation which obstructed north-south trade. Merchants and agriculturalists now looked east and west with renewed interest for a tariff-free route to prosperity.

The hero of canal construction on the Peterborough section of the Trent-Severn waterway was Richard Birdsall Rogers, who, along with Walter Francis, his Divisional Engineer, worked against impossible timelines, shortages of skilled labour, and bureaucratic interference. The innovations which Rogers proposed and successfully executed, from concrete dams to the dry mix cement technique to the design of the highest hydraulic lift lock in the world are all due to his engineering genius and enterprising spirit. The firm of Corry and Laverdure won the concrete contract for the Lift Lock and Dominion Bridge was responsible for the superstructure. The fall of the Conservative Government in 1896 and the advent of the Laurier Liberals was an ominous event. Work on planning, designing and then building the Lift Locks continued but political machinations affected each and every step from hereon. Men who worked on the canal were interviewed in the 1960s.(5) They commented on their salaries ($1.00 per day and $1.50 if you also supplied a team and horses); on the fact that Laverdure had no education or experience when he took on the cement work.

The Peterborough Lift Lock was officially opened on July 9, 1904. Leah Geale, daughter of R.B. Rogers noted in an interview that it rained so hard on opening day that people standing on the banks near the towers of the Lift Lock slid down the hill as the newly-laid sod slipped its moorings. The dyes in the ribbons of women’s bonnets dissolved in the rain, ran down their faces and ruined their dresses. R.B. Rogers was disappointed that the contingent of officials from Ottawa were only going to stay in Peterborough for the day of the opening but, these minor trials notwithstanding, Opening Day was a huge success.

Notes

1 Michael Peterman, My Old Friend the Otonabee: Glimpses by Samuel Strickland, Catherine Parr Traill and Susanna Moodie (Peterborough: Peterborough Historical Society Occasional Paper 20, October 1999) p.4

2 Wendy Cameron and Mary McDougall Maude, "Setting the Scene: Canals in Upper Canada," in Wendy Cameron and Mary McDougall Maude, eds. Essays and Research Papers on the History of the Trent-Severn Waterway, (Ottawa: Canadian Parks Service, Environment Canada, vol. 1, 1987) p. 25.

3 Jean Murray Cole, ed., The Peterborough Hydraulic Lift Lock, (Peterborough: Friends of the Trent-Severn, 1987) p. 7.

4 http://www.trentu.ca/library/archives/82-006.htm, tape 15, interview with George Noyes.

5 http://www.trentu.ca/library/archives/82-006.htm

Bibliography

Angus, James T. A Work Unfinished: The Making of the Trent-Severn Waterway. Orillia: Severn Publications, 2000.

Cameron, Wendy and Maude, Mary McDougall. Essays and Research Papers on the History of the Trent-Severn Waterway, Vol. 1 and 2. Ottawa: Canadian Parks Service, Environment Canada, 1987 and 1988.

Cole, Jean Murray, ed. The Peterborough Hydraulic Lift Lock Peterborough: Friends of the Trent-Severn Waterway, 1987.

Coleman, J. The Settlement and Growth of the Otonabee Sector. Trent-Severn Waterway Interpretive Program Publication 14. n.p., n.d.