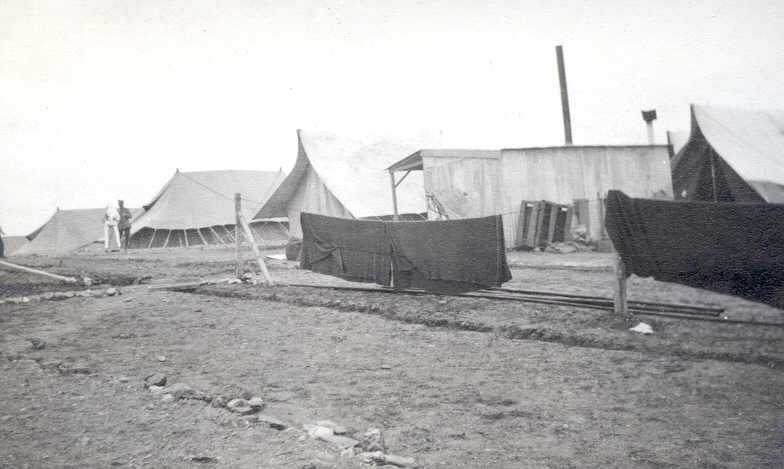

Sister's Mess

Though nurses had served only sporadically and in small numbers in the Northwest Rebellion and the Boer War, by the First World War, the services of a nursing unit were seen as vital to the Canadian Medical Corps. For the modest sum of $4.10 per day and a belief in serving their country, graduates from all the major training hospitals across Canada volunteered. By August 17, 1914, Nursing Sister Margaret C. Macdonald was in Ottawa putting together a list of qualified nurses and on September 16 the order to mobilise was received. Ninety-eight Sisters were ordered to Valcartier, Québec on September 23 where they were examined to make sure they were physically fit, attested, inoculated, vaccinated and outfitted. This first group embarked for England on the Franconia on September 29. A second group including Helen Fowlds sailed from Halifax in February, 1915 on the S.S. Zeeland.

All Canadian nurses entered the Army Medical Corps at the level of "Lieutenant" unlike their British colleagues. Matrons entered at the level of "Major." Their uniforms were sky blue cotton with the two First Lieutenant’s stars on the shoulder. White aprons with straps crossed in the back went over the long dress. Sheer white veils were worn while on duty. The dress uniform was navy blue serge. They wore navy blue jackets with a high round collar edged with scarlet and white. For inclement weather, there was a long navy coat or a navy cape lined with scarlet. Army-issue black boots completed the outfit but Helen Fowlds notes in one of her letters to her mother that while running to the hospital tents in pouring rain she wore a sou’wester, galoshes and her skirts hiked up to her knees. She is careful to say, however, that once on duty she was in proper uniform once more.

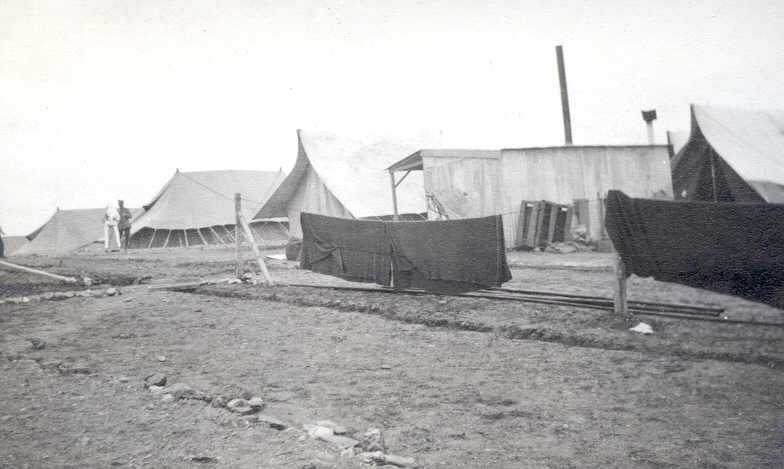

Sister's Mess

Nurses were deployed throughout a number of different types of facilities. In the initial phase of the war, casualties were treated in regular hospitals in France and Britain. Soon, 4 Casualty Clearing Stations were set up near the front in order to assess the condition of the wounded and give them immediate emergency treatment before moving them to hospital. There were approximately 200 beds in these Stations. Canadian General Hospitals were initially located in Le Tréport and Étaples. There were soon 14 Canadian General Hospitals in operation. Each of these were permanent sites with, ideally, 1,040 beds each. Canadian Stationary Hospitals which eventually numbered 10 were in fact mobile units which, as Helen Fowlds notes, renders the name somewhat ambiguous. These units could move up towards the front or remove casualties to safer locations. They were employed in such places as the Dardanelles where troops were being evacuated as well as in France. In addition to these Canadian hospitals in Europe and the Balkans, there were 8 hospitals in Britain specified for the treatment of Canadian casualties. Nurses who had trained together at schools of nursing in Canada generally served together in medical units. For example, the No. 3 Canadian General Hospital was made up of surgeons and physicians from Montreal and McGill Universities. Nurses in this unit were from the Royal Victoria and Montreal General Hospitals. Similarly, No. 5 Stationary was comprised of Queen’s University nurses; No. 7 Stationary nurses were from Dalhousie and No. 6 General Hospital was staffed by Laval University nurses. Helen Fowlds had graduated from Grace Hospital in Toronto and served with graduates from Toronto General Hospital.

By the end of the war, 2,504 Canadian nurse volunteers had served overseas with the Canadian Army Medical Corps Nursing Unit in England, France, Gallipoli, Alexandria and Salonika. They treated every sort of wound and devised new techniques for handling the administration of anesthesia in the field. They comforted and tended patients under active battle conditions. They cared for patients with dysentery and frostbite after the evacuation of Gallipoli. They themselves were not immune from the pandemic of influenza which swept the world in 1918 and 1919, nor the periodic outbreaks of spino-meningitis. Forty-six were killed in the line of duty. On May 19, 1918 No. 1 Canadian General Hospital in Étaples was bombed. The hospital was at full capacity at the time with 2,218 patients being cared for by 142 nurses. There were 56 fatalities including four nurses killed and many others injured. No. 3 Canadian Stationary Hospital at Doulens was hit on May 29, 1918 with two nurses killed. On June 27, the Canadian Hospital ship Llandovery Castle was torpedoed and sunk. All fourteen nursing sisters on board were drowned. Other nurses were killed by disease.

In 1919, the Canadian Nurses Association decided to raise funds for the design and erection of a memorial in honour of nursing sisters of World War I. G.W. Hill R.C.A. was the artist chosen to execute the monument which is located in the Hall of Honour, centre block Parliament Buildings, Ottawa. It was unveiled in 1926.

1. Clint, M.B., Our Bit: Memories of War Service by a Canadian Nursing Sister

(Montreal: Barwick, 1934).

2. Gibbon, John Murray, Three Centuries of Canadian Nursing (Toronto:

Macmillan Co., 1947).

3. McPherson, Kathryn, Bedside Manners: The Transformation of Canadian Nursing,

1900-1990 (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1996).

4. Nicholson, G.W.L., Canada’s Nursing Sisters (Toronto: Samuel Stevens,

Hakkert, 1975).

5. Wilson-Simmie, Katherine, Lights Out: A Canadian Nursing Sister’s Tale

(Belleville: Mika, 1981).

Go to Exhibit Home Page